Blended, not binary - creating a diverse and representative curriculum

By Alex Fairlamb (@lamb_heart_tea) | Seneca Curriculum Conference | 23 Oct 2021

On the 23rd of October 2021, Seneca hosted a free virtual conference about the Curriculum, featuring four incredible speakers and 800 signed-up attendees!

You can watch the recording on our YouTube channel here and access the slides here.

Below, it’s the article written by Alex Fairlamb, one of the speakers, as a summary of her talk.

What do we mean when we talk about diversity in the curriculum? A truly diverse curriculum is one that is representative of the communities that we serve, and it is one that ensures that is inclusive as much as it is broad and balanced. This includes gender, race and ethnicity, LGBTQ+, disabilities (visible and non-visible), faiths, disadvantaged backgrounds, and other characteristics.

The importance of having a diverse curriculum cannot be overstated. As Reid states “we have a duty to offer a curriculum that allows students to access what I have termed the ‘broader picture’: learning about the canon (or the facts of the dominant discourse) but also how it came to be that way. In order to achieve this, there needs to be a conversation in the curriculum between what the traditional canon is made of and what has often been excluded. Considerable thought needs to be given to how this weaves together as a whole narrative, as I believe it is in this whole that the transformative potential for students and their communities lies. (Reid, 2020)” Lets’ deconstruct this:

(You can watch Alex’ full talk above)

It is our duty of care to ensure that as architects of the curriculum, that what we select from the domain of our subject disciplines to teach is representative and diverse.

This will have a significant and positive impact on our children, who will see themselves within the curriculum. As Reid further argues “I believe it is a matter of intellectual integrity to insist on reading these voices together. By understanding how the world works, they also get to have a stake in it. They can see that the world is not something done to them but something that they are part of” (Reid, 2020).

The canon is there but it excludes much. As practitioners, we need to fully audit and evaluate what we teach and ensure that we develop the curriculum beyond the canon. That is not to say that we throw the baby out with the bathwater and reject the canon completely. It means taking this as part of the curriculum and then enriching it beyond this. This might include uncomfortable truths as we realise that what we have taught previously has perhaps not met the needs of ALL of our students. However, we need to get comfortable with being uncomfortable when evaluating our curriculum in the vein of Angelou’s “when we know better, we do better.” Just as once upon a time we used VAK (Visual, Audio, Kinaesthetic) principles within teaching and learning, we now look back uncomfortably knowing that this pedagogy is incorrect. Once we know something isn’t meeting the needs and we have educated ourselves, then we action it.

To ensure that we move further towards an inclusive society that is rooted in mutual tolerance. To do this, we need to ensure that we educate children about all members of our world, not just dead, white English men.

Cultural capital. The big phrase of the past year. The ‘canon’ is too often seen as the key criteria for ensuring that children have cultural capital – that they know classical composers such as Mozart and authors such as Dickens. However, as Caroline Criado-Perez (Criado-Perez, 2019) identifies, the canon ignores the social and cultural constructs that prevented the canon to be beyond what it came. Mendelssohn’s work was sometimes written by his sister Fanny, for which he lays claim as the patriarchal society at the time did not permit women to become composers. Dr. James Barry, a trans person, was an incredible war surgeon who performed the first cesarean where mother and child lived, however does not feature in the ‘History of Medicine’ as at the time society rejected and persecuted trans people. What makes it such that we should learn about the work of Pare but not Barry? GCSE and A-Level specifications are very guilty of not being diverse, but conversations are beginning to happen. The canon needs rethinking and updating.

How then should we approach evaluating a curriculum and developing it as a leader?

The first step should always be to educate yourself further within all the disciplines. Listen to your departments and have conversations, encourage departments and other leaders to read texts such as The researched Guide to the Curriculum, and also look at your student and local area demographic e.g. in Teesside - are the Romany traveler communities represented?

Look at your curriculum vision. Does it need changing? Why and how? The key to this is to avoid trying to fast-track changes and accidentally adopt a tokenistic approach. Curriculum evaluation needs careful consideration, meaningful construction, and several “let’s look at this again, have we met our vision and the needs of our communities?” moments.

For me, my approach to it will always be ‘blended, not binary’. Diversity should not be a bolt-on to the curriculum where it is shoehorned into a scheme of learning to tick a box, nor should it be confined to calendar days alone. Hamer (Hamer) identifies clear stages whereby we can determine how we are ensuring that our curriculums have diversity meaningfully woven through and how we can avoid ‘diversity drops’ as I call them (where diversity is just dropped in and the mainstream curriculum has bolt-ons added to it).

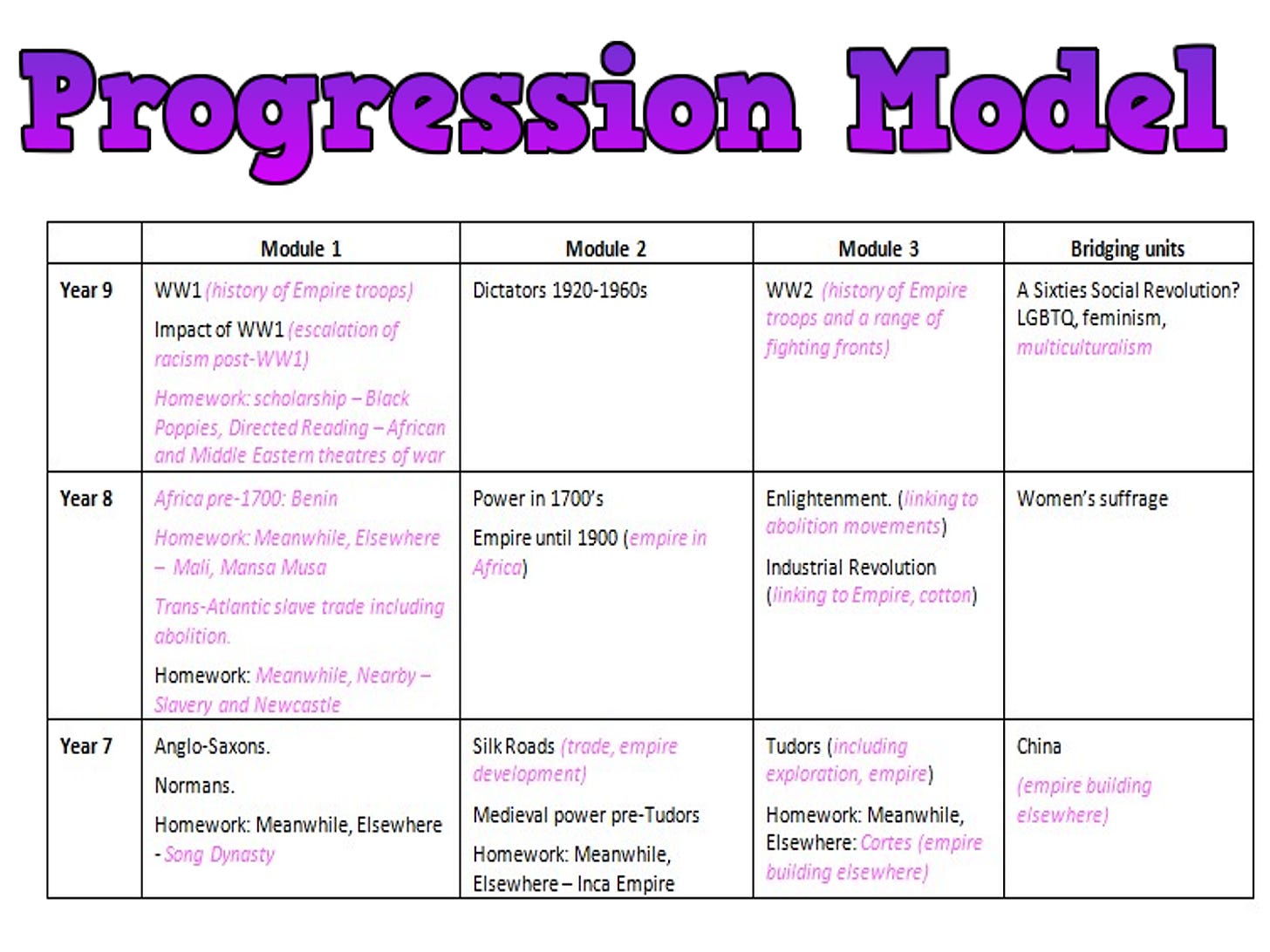

How might that look in practice? History KS3 case study.

The department that I am in established the vision for the department which included ensuring that the history that we taught was diverse and as Counsell states “Britain as part of the world and not the centre of it”.

Resultantly, we ensured that the construction of our new curriculum was diverse, challenging and that we set high expectations of ourselves and our students in the content that we studied, supported by scholarship. Threaded all throughout our curriculum is representative history. Prior to our changes, the Silk Roads and the development of the Islamic world were not taught. Now it is and we can trace this development from Year 7 all the way to our studies in GCSE when we study the History of Medicine (Islamic medicine). Likewise, previously our studies of Africa had been focused on the slave trade and the British Empire.

Now, we study medieval African cultures by focusing on countries such as Song, Mali, and Benin. This then threads through to the slave trade (where we have enhanced the focus on maroons and resistance), empire but then further into Year 9 where we explore the contribution of Empire troops (with students studying texts such as Black Poppies), the rise of anti-immigration racist attitudes post-WW1 in Britain and America, the contribution of Empire troops in WW2 (for example, the Muslims of Dunkirk) and then civil rights in America and also the extent to which Britain became a more multicultural society by the 1960s by exploring Empire Windrush through to history such as the Race Relations Act. We ensure that we explain to the students why we are studying diverse history and our Benin SoL begins with dispelling myths about Africa (for example, it’s a continent of many countries with different languages, cultures, and religions – not a continent!). Within this, we are also mindful of the language that we use, such as using ‘enslaved African’ rather than ‘slaves.’ Is our curriculum perfect? No, but we will continuously evaluate as we go through each iteration and improve it as we do.

Next steps:

Wider reading and connect with peers

Engage staff in unconscious bias training

Support staff to engage in subject-specific CPD which explores these issues, such as the Historical Association, TMIcons, and Seneca subject training.

Work with teams – you are the architect of a curriculum – what narratives and key elements do you think are essential to ensure a broad, diverse, and balanced curriculum in their subject discipline?

Audit your current scheme of learning.

Look at topics with multiple lenses

Work with others to challenge the canon – how can we push for this change on a national scale e.g. with examination specifications and the National Curriculum?

Consider:

Be realistic with time and content – selection, connection, representation (can’t include EVERYTHING so expertly choose WHICH)

Blending, not bolting on – blend not separate

Maintaining individual experiences – ensuring that the blend doesn’t result in the loss of narratives

Homework and independent learning to develop understanding

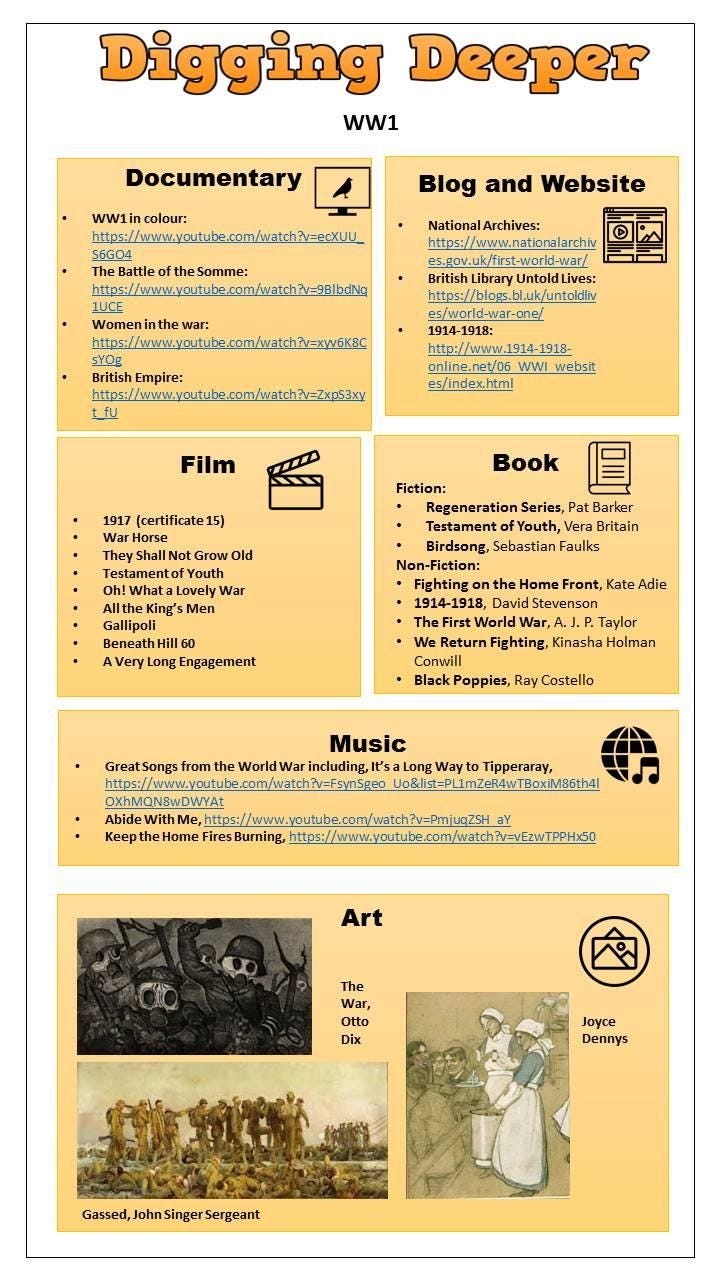

Digging Deeper – curiosity and wider learning. Creating sheets that engage the children further into the content in a multi-media way.

References

Criado-Perez, C. (2019). Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men. Random House.

Hamer, J. (n.d.). Gender Issues in Teaching History.

Reid, A. (2020). Cultural Capital, Critical Theory and Curriculum. In C. Sealy, The researchED Guide To The Curriculum. John Catt Edu.

Alex Fairlamb is an Assistant Headteacher of T&L and s former History Lead Practitioner. She is an ELE and SLE and specialises in History and metacognition. She is National Coordinator for TMHistoryIcons and she is a member of the Historical Association Secondary Committee. She is committed to diversity and equality and she is the Lead Teacher for GirlKindNE. Follow her on Twitter @lamb_heart_tea