A whole school framework for Teaching and Learning: Why, What and How

By Alex Gordon @MrAWGordon_ | Seneca Virtual Conference | Curriculum: The Big Picture | 23 Oct 2021

On the 23rd of October 2021, Seneca hosted a free virtual conference about the Curriculum, featuring four incredible speakers and 800 signed-up attendees!

You can watch the recording on our YouTube channel here and access the slides here.

Below, it’s the article written by Alex Gordon, one of the speakers, as a summary of his talk.

This is our journey through implementing this framework and is by no means a revolutionary concept or a complete entity yet, it is a work in progress and one approach to Teaching and Learning across a school.

The presentation was structured in three parts:

Why is it important?

What did we put together?

How is it being implemented and embedded?

Why is it important?

Why is a consistent and overarching Teaching and Learning framework important?

Clear ‘time and space’.

Ensure consistency across classrooms.

Remove obstacles for teachers.

‘Every minute counts’ to ensure lesson time is productive and not wasted.

Support a cultural sense of collective responsibility.

It is strongly believed that teachers do need to feel they have freedom within the classroom but as part of a whole school framework to support outcomes and ensures the best possible education for pupils. A study from the NFER published in January 2021 found that ‘teachers are 16 percentage point less likely than similar professionals to report having ‘a lot’ of influence over how they do their job’ and that ‘teacher autonomy is strongly associated with improved job satisfaction and a greater intention to stay in teaching’. My initial starting point here was a blog post written by Louis Everett around a whole school framework for classroom systems and Teaching and Learning.

”Academic success is based on a solid foundation of curriculum, excellent behaviour, pastoral work and whole school routines. This is supported by a whole-school framework for classroom systems and Teaching and Learning with a shared language so rationale and logistics are understood by all.”

Without a clearly understood and shared whole school framework, there is no guarantee that every teacher can have this autonomy to teach their best. A lack of consistency across classrooms means that students may experience five different routines or systems in any given day. Some of these routines may be embedded, some not which impacts the time in the classroom where students should be learning.

This approach links heavily to our goal to be evidence-informed in our practice. This ven diagram ensures that within this approach, we are utilising the expertise we have within our school but also ensuring we acknowledge and give importance to the context and demographic of our setting. Scutt (2018) argues that ‘evidence-informed practice is about drawing on research, but also considering it in context and balancing it with existing experience, expertise and professional judgement. In this way, it becomes a means of helping teachers to understand some of the problems that they are facing in the classroom and offers testable strategies to improve teaching and learning. At the heart of evidence-informed practice is the effort to reduce the guesswork around ‘what works and why’.

A further proponent of this whole school framework for Teaching and Learning is Bruce Robertson (author of the Teaching Delusion) who states:

”A clear and shared understanding of what makes great teaching is essential to improving the quality of teaching in classrooms and schools. Without this, different teachers will teach in different ways – some effectively and some less so… the quality of teaching will vary widely. Without a shared understanding… you might know what you are trying to achieve, but you don’t know how to achieve it.”

What did we put together?

We were very conscious that any Teaching and Learning whole school framework was created by all and not a top-down model. Therefore, in order to establish and created a share language, we put together a Teaching and Learning Council in the last academic year. The only four requirements of any potential applicant was a willingness to learn and lead, commitment and enthusiasm to Teaching and Learning. There was no formal ‘interview’ here and we appointed 12 members to the council from a range of different subjects and experience levels. This included Heads of Department right down to NQT’s.

In order to put together a set of ‘Great Teaching’ Pedagogical Principles to ensure a Teaching and Learning framework, we followed the following process.

At the ‘Creation and Analysis’ stage after we had discussed the rationale and explored current research, I asked the members of the council three questions.

What must be included within our Pedagogical Principles?

What would you like to be included within our Pedagogical Principles?

What shouldn’t be included within our Pedagogical Principles?

Here are some of the responses to the third question which massively impacted the creation of the Principles.

What shouldn’t be included within our Pedagogical Principles?

• A list of expectations of that are used to hold teachers accountable.

• A list of demands placed on teachers that narrow subjects and all they do is burden teachers with more work and more ways of being scrutinised.

• Principles should not be prescriptive as different subject areas have different priorities – however there should be an obligation for each subject area to develop a ‘best fit’ for each principle, ie ‘In AD Principle X looks like’ which should become dept standard practice.

• Principles that have low impact or have limited evidence of effectiveness.

• Principles not based upon evidence of ‘best bets’.

• These principles should not define in any way actual activities (e.g. quizzes, cold calling, exit cards) otherwise they are not principles but methods. They should not dictate lesson structure, allocation of lesson time, and I would be wary of them becoming an observation tool (lesson observations are dubious in their effectiveness anyway) – I would envisage them as a reflective guide for staff to use in the scrutiny of their own practice.

Once we had discussed these questions and had a framework to work with, we were ready to design the layout and visual look of Principles.

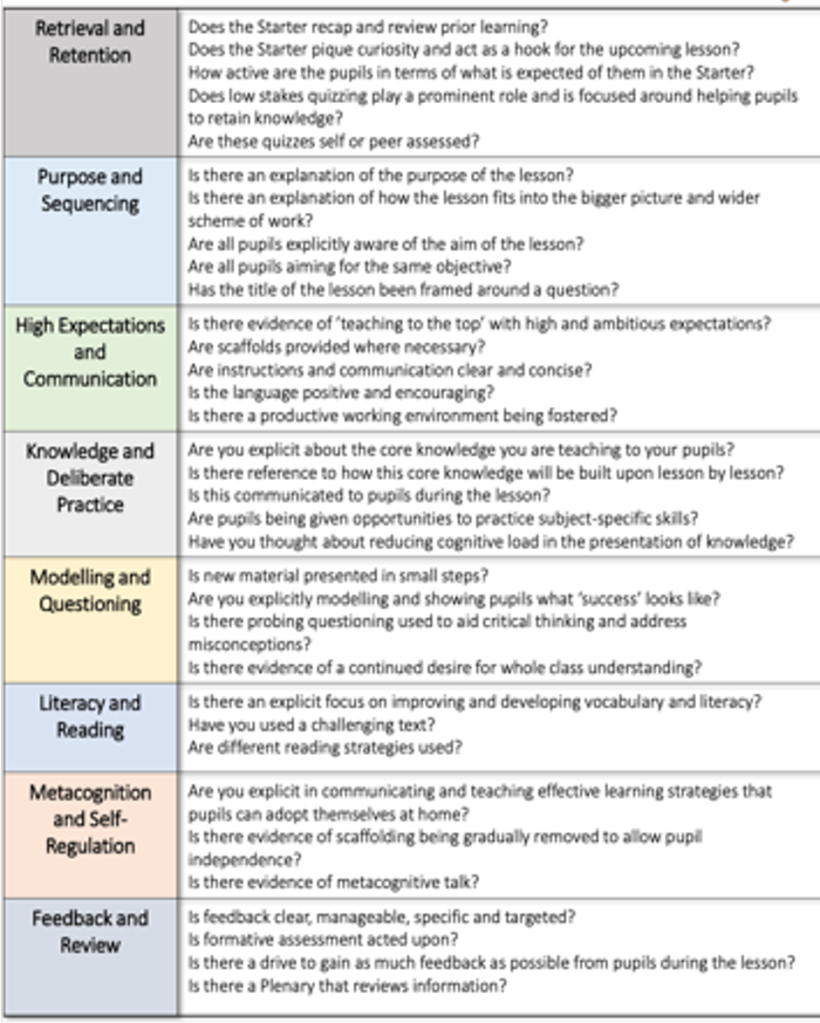

Teacher autonomy relies on a framework of whole-school classroom routines and systems, with a shared language so the rationale is clearly understood. Within this framework teachers can be themselves, the knowledgeable, charismatic, autonomous subject-experts. The Principles are what the school has identified as ‘Great Teaching’ across their classrooms. They are inclusive and show an awareness of the needs of all learners. ‘Eight components’, driven by research, collaboration and staff experience have been identified and agreed by staff representing a set of common features that, typically, produce high-quality teaching. The Principles are not a checklist or prescriptive and there is no requirement that every lesson should be framed around all eight.

How is it being implemented and embedded?

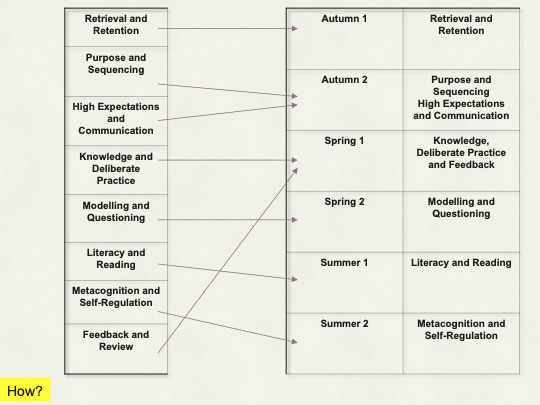

After a period of consultation with all staff at the end of 2020-21, the Principles were formally launched through the different CPD programmes and will support a shared staff language tying together and helping to ensure a consistency of excellence across all classrooms. To embed them within our culture, each Half Term will have a separate focus based upon the Principles.

We were very deliberate with our meeting structures and CPD time to ensure that the Principles are at the heart of our Teaching and Learning programmes and discussions.

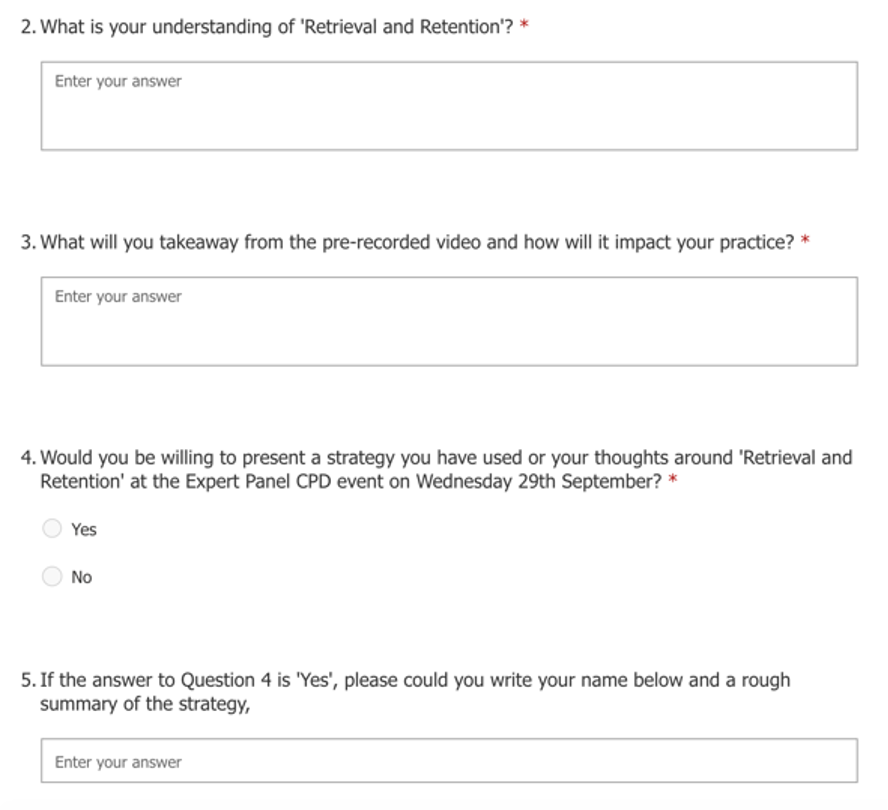

At the start of each Half Term, a one page research document is shared with staff (alongside a pre-recorded video) to explicitly present the research behind the Principle. The first one on ‘Retrieval and Retention’ can be found here and the second one on ‘Purpose and Sequencing, High Expectations and Communication’ can be found here. After this, we share a Microsoft Form with staff to gain their reflections on the Principle and to also canvass staff views on who would like to volunteer to present at out CPD Expert Panel event.

Alongside this, we also asked Heads of Department to informally RAG their departments against the Principles to see where further support can be given and where departments are strong in an area, to see what best practice can be shared across the school.

Our CPD Expert Panel event involves a number of teachers presenting their own personal strategies explicitly linked to the Half Term Pedagogical Principle focus. A branded poster is shared in advance of the event.

In order to further support the implementation of the Principles, we have a visual Teaching and Learning noticeboard in the staff corridor with key reminders and the Half Term focus explicit. This is alongside a Teaching and Learning CPD library.

Within our interconnected CPD curriculum and our five strands approach (more information on this can be found here and here), we explicitly reference the Principles.

However, there are a number of areas to be careful of in relation to a Teaching and Learning framework. It is important to consider these in any creation or implementation.

Subject specificity

‘All in’ not top-down

Embedding, embedding, embedding…

Spaces for discussion and feedback

A framework liberate and supports autonomy… how does this work and how is it understood?

To read more from Alex, visit his blog and follow him on Twitter @MrAWGordon_